Deep Life Reflections: Friday Five

Issue 96 - Anatomy

Welcome to Issue 96 of Deep Life Reflections, where I share five things I’ve been enjoying and thinking about over the past week.

What shapes how we see the world—others, or ourselves? This week, Juliet Triet’s award-winning film Anatomy of a Fall and Ian Jeffrey’s superb How to Read a Photograph examine the many layers of interpretation, showing how truth is subjective and relationships, like photographs, depend on perspective. What do we see when we look closer?

Join me as we explore this week’s Friday Five.

1. What I’m Reading

How to Read a Photograph. By Ian Jeffrey.

Photography can defeat time. Images can preserve the memory of those closest to us, freeze a moment in history for future generations; and be an observer of acts of tragedy or joy. Photography is often seen as a window to reality, but it’s so much more. When we look at photographs, we don’t just look at them passively; we search for meaning. Ian Jeffrey’s How to Read a Photograph—a beautiful hard-cover gift from a friend—reveals that photography is more like a language; a visual text we read just as we would a piece of writing. And not just read, but also interpret and feel.

Look at any photo from your past—perhaps a holiday, a celebration, or even something random and inconsequential. It likely stirs a feeling, perhaps something you haven’t felt in a while. As someone who loves both photography and writing—and as someone always looking to improve in both—this book offers not just an education but also an invitation to think differently about the images we create and consume.

Jeffrey journeys through the pioneering work of over one hundred great photographers, cataloguing the history of photography as an art form. He explores how meaning is embedded in an image, almost with forensic precision. As he explains, we don’t just look at photos, we read them—searching for clues, deciphering symbols, and attempting to understand the context in the same way we would unravel the subtext of a novel or poem. Photographs aren’t just static images; they represent dynamic narratives filled with intent, emotion, and cultural resonance.

Photographer Stacy Kranitz once said, “Photography becomes an ideal medium to navigate ideas around humanity, connection, identity, memory, presence, experience and intimacy.”

This philosophy comes to life in the work of iconic photographers like Alfred Stieglitz, Bill Brandt, and Henri Cartier-Bresson. Jeffrey dissects their work with exactness and care, examining how these masters used light, composition, and timing to tell stories that endure far beyond the frame. He starts with William Henry Fox Talbot, the British scientist and photographer who made the first photographic negative in 1835. His subject was a lattice window in his home in Lacock Abbey, England. Even today, that photo has a serenity and sense of wonder, an idea of both discovery and permanence—the very foundation of what photography would become.

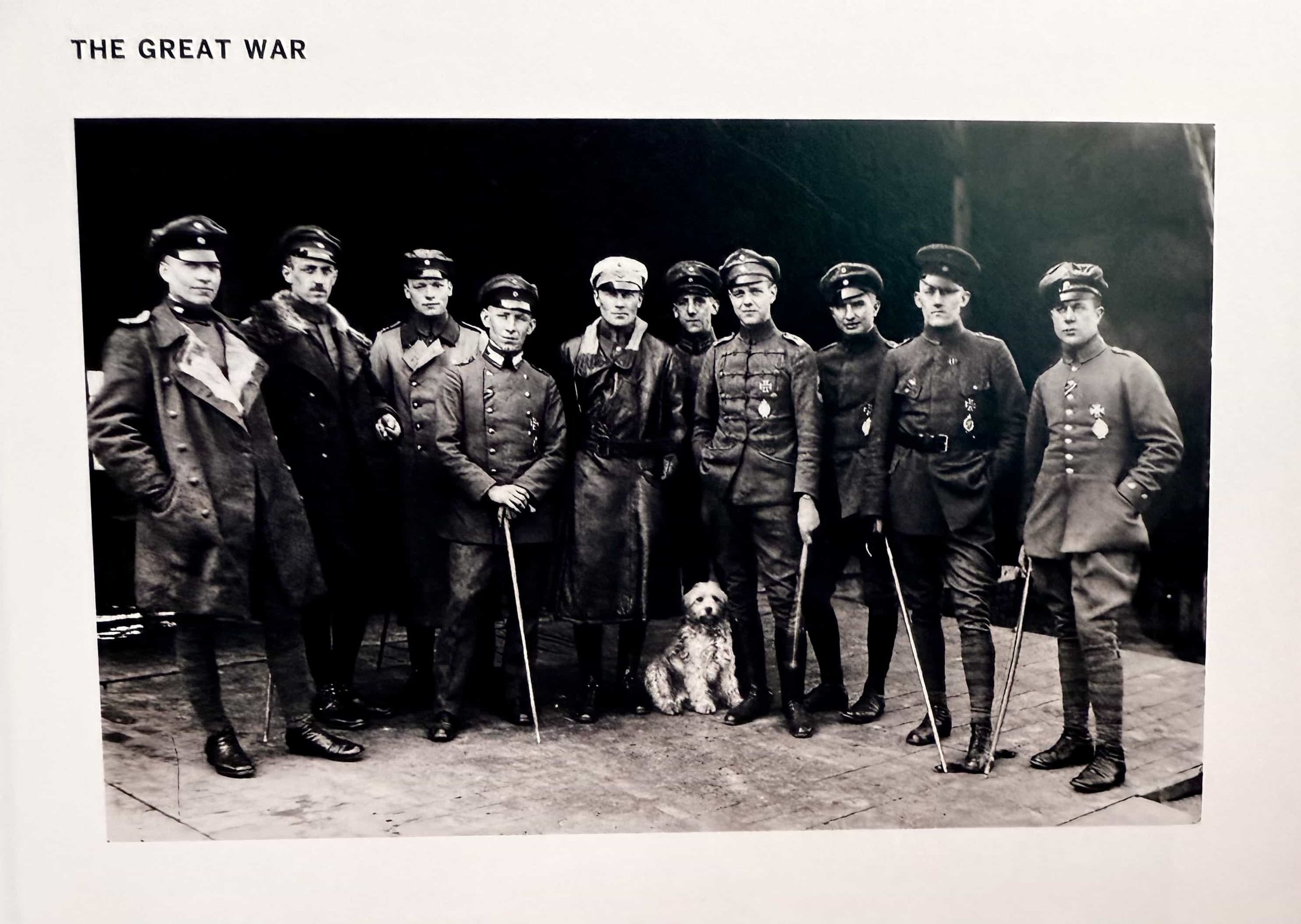

An excellent section on the Great War showcases the character of war and those who lived it. In German Pilots, pictured below, Wilhelm Von Thoma captures ten men standing as they please, resplendent in their uniforms and individuality. Pilots in the first world war constituted a new aristocracy—the aviators. Steeped in charisma and technical skill, these aviators set in motion the idea of the ‘star’ that later flourished in film between the two wars.

German Pilots by Wilhelm Von Thoma

Like great literature, How to Read a Photograph doesn’t impose an interpretation. Jeffrey offers his view, but allows each image to stand alone, uncategorised, inviting us to bring our own perspectives and experiences to what we see. As we reflect and think deeper, it recalls that other truth about photography: it is as much about the viewer as it is about the maker.

And we all have stories to read.

2. What I’m Watching

Anatomy of a Fall. Directed by Justine Triet.

Winner of the Palme d’Or at Cannes, Anatomy of a Fall is a textured exploration of truth, perception, and the slow, devastating unravelling of a relationship. Directed by Justine Triet, who became the eighth woman nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director, the film examines the aftermath of a man’s death, Samuel—his body discovered by his partially blind son, Daniel, at the base of their home in remote and snowy Grenoble, France. His wife, Sandra (played by German actress Sandra Hüller in an outstanding performance) becomes a suspect, and the story becomes her trial. The court attempts to answer the central question: was his fall an accident, suicide, or murder?

Sandra’s character is a study in ambiguity. We’re never really sure about her guilt or innocence, and we’re given little evidence that support either. Triet instructed Hüller to stay in an emotional arc that avoided clear guilt or innocence. As a result, Sandra remains remote and elusive, a woman impossible to fully know. This detachment is mirrored in the cold, isolating setting of Grenoble, where the frozen, barren landscape becomes a metaphor for the emotional distance within the family, especially with her son Daniel, called as a witness in the case.

Communication plays a central role in the film. Sandra and Samuel communicate in English, a second language for both, adding layers of miscommunication and distance. Meanwhile, Daniel, struggling with impaired vision after an accident—an accident Samuel feels guilty for and may be harbouring suicidal tendencies—becomes a symbol of the film’s broader theme: we don’t fully understand each other nor do we fully see one another.

Anatomy of a Fall is fundamentally about the unknowable nature of relationships, particularly in marriage. How well do we ever really know those closest to us? The title itself serves as a metaphor: ‘the fall’ reflects both the physical tragedy and the slow-motion collapse of a marriage, while the ‘anatomy’ refers to the painstaking dissection of every moment, motive, and interaction between Samuel and Sandra. The courtroom becomes a stage where the remnants of a life are laid bare—messy, fragmented, and open to interpretation.

One of the film’s best scenes, actually a pretty devastating one—an argument between Sandra and Samuel—is experienced through a clever plot device: an audio recording made by Samuel weeks before his death, played back for the jury. We, as the audience, become silent observers, a kind of ‘super jury,’ interpreting the anatomy of their communication. What do we see and hear? Resentment, pity, infidelity, and the breakdown of a partnership. It’s sad because it feels like one of many such interactions, each one adding a cruel weight to their collapsing relationship.

Triet draws inspiration from real-life cases, including the notorious Amanda Knox trial, adding themes of public scrutiny and personal identity into the core of the story. As Sandra’s life is examined under the court’s microscope, it begins to feel as though her personality, as much as her actions, is on trial. This is also what gives the film its acclaim—it’s lack of moral signposting. It’s also no melodrama—we don’t even hear the final verdict, only the press conference a few minutes later. While there is a puzzle to solve, I don’t believe this is the crux of the film.

Anatomy of a Fall isn’t about solving the mystery of a death—it’s about the anatomy of a marriage and the impossibility of ever truly knowing another person. It’s about the struggles of effective communication and what that failure can lead to in its worst form. We feel the chill and the cold. We feel the warmth drained from the family and the clinical steel-tipped anatomy of the trial.

Even when all the pieces are in place, the answers remain just out of reach.

3. What I’m Contemplating

Both works this week examine the complexity of interpretation—whether in the anatomy of a relationship or an image.

Anatomy of a Fall captures the subtle erosion of a relationship, mirrored by the barren landscape that reflects the growing emotional distance between two people. Ian Jeffrey’s How to Read a Photograph, with his meticulous analysis, explores how photographs reveal layers of meaning, depending on how deeply we look—and how differently we interpret the same image. Both works suggest that truth is subjective, shaped by personal experience and context.

I saw something interesting this week—Life in Another Light, a photography contest for the best infrared photography. The winning photo, Switzerland, pictured below, reframes a familiar Swiss mountain scene as something entirely new: a fluorescent pink foreground framed against a normal mountain range. It’s a stunning and other-worldly contrast, kind of freakishly beautiful. It reminds us that what we see depends on how we choose to look—and what tools we use to uncover hidden layers of meaning. Photography provides us with new perspectives about our world.

Switzerland by Gavin Spooner

In an age dominated by smartphones and our vast digital library of thousands, it feels like we are losing the power of the photograph, at least individually. The ‘photo dump’ phenomenon reflects this shift—no longer are photos curated to preserve meaning; they are shared en masse, consumed in seconds, then forgotten, consigned to a bottomless digital well.

With all these digital memories, we risk drowning in moments that lack meaning. Perhaps we require some kind of ‘digital sieve’ to sift through the noise and carefully curate what matters. Memories that anchor us to people, places, and moments—just as photography once did.

Whether in the anatomy of relationships or photography, meaning comes from careful observation and intentional focus. Without it, we lose the layers of truth, connection, and beauty that make life rich.

And sometimes pink.

4. A Quote to note

“We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.”

- Anaïs Nin, from her 1961 work Seduction of the Minotaur

5. A Question for you

If you could curate a photo collection of your life’s most meaningful moments, which three would you choose? (Go ahead and do it 📷)

Thanks for reading and being part of the Deep Life Journey community. If you have any reflections on this issue, please leave a comment. Have a great weekend.

James

Sharing and Helpful Links

Want to share this issue of Deep Life Reflections via text, social media, or email? Just copy and paste this link:

https://www.deeplifejourney.com/deep-life-reflections/january-17-2025

And if you have a friend, family member, or colleague who you think would also enjoy Deep Life Reflections, simply copy, paste and send them this subscription link:

https://www.deeplifejourney.com/subscribe

Don’t forget to check out my website, Deep Life Journey, for full access to all my articles, strategies, coaching, and insights. And you can read all previous issues of Deep Life Reflections here.